“How many jellybeans are in a pound of candy?”

“How many bubbles are in a bar of soap?”

“How many feathers are on a chicken?”

When Flonzie Brown Wright went to register to vote in 1960s Mississippi, she faced “crazy questions” like these when the white registrar threw her a two-page, 21-item questionnaire. Despite “dressing up” that day and thinking “I was about to become a first-class citizen,” there were components of her registration experience for which she could not properly prepare.

Citizens of color were asked “anything that the registrar dreamt up on a particular day,” Wright reflects in an interview with Voices of the Civil Rights Movement. The test for white citizens was limited to: name, address, employer, Social Security number, and “maybe one or two other questions.”

When asked to define “habeas corpus” as it was written in the Mississippi Constitution, Wright didn’t have the answer. She recalls, “I wrote something because I was hoping that if he was having a good day, that he would allow me to pass.”

When Wright was told she didn’t pass the test and asked why, the registrar responded, “N-----, I told you, you didn’t pass. You get the hell out of my office.” Wright continues: “The day that I left the courthouse, and I walked down the corridor, I decided that I would run for public office — and I knew that I was going to win.”

Wright decided to run for Election Commissioner in “Beat 1” in Canton, Miss. Once she qualified, the election commission changed the requirements, declaring she needed to run in all five beats in Madison County. She reflects this move was “another way of trying to defeat me.”

But she was undeterred — she pushed on to meet the new requirements to run for office, and ultimately won the election. On Nov. 5, 1968, Wright became the first Black woman elected to public office in Mississippi, post-Reconstruction, as the Canton Election Commissioner.

It was a historic moment — one Wright was keenly aware would not have been possible without untold numbers of voting rights activists who began and sustained the fight for the vote.

VOTING RIGHTS BEFORE THE CIVIL RIGHTS ERA: A CENTURY-LONG FIGHT

The U.S. Constitution was adopted in 1789, after the first federal elections in the U.S. The right to vote was not codified in the Constitution, and states were left to determine voter eligibility. At that time, mostly white, land-owning males had the right to vote. In 1870, Black men gained the legal right to vote, but many states did not allow Black men to exercise their right. The white suffragists of the late 19th and early 20th century, campaigning for women’s right to vote, “made a conscious decision to exclude BIPOC women from their movement,” notes PBS Teachers Lounge. Still, Black women and women of color stood up for their voting rights, including Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Zitkala-Sa, a member of the Yankton Sioux Tribe of South Dakota, and Sojourner Truth. When women gained the legal right to vote in the 19th Amendment, discrimination against Black women made it difficult for Black women to exercise their right.

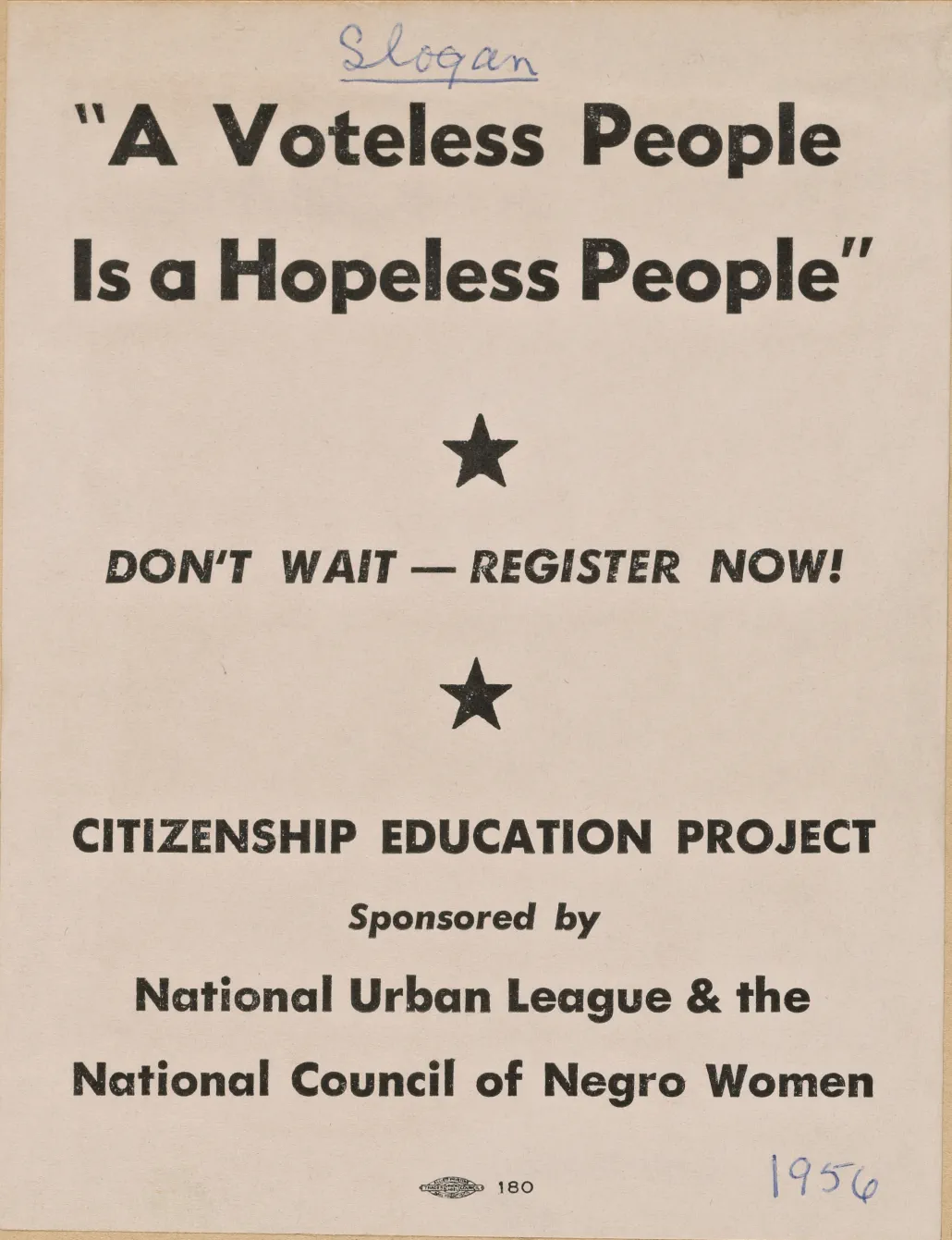

To bridge the gap between the law on paper (19th Amendment) and the law in practice (voting at the polls), women’s suffragists like Frances Albrier and Dorothy Height continued the next phase of the fight. In the late 1930s, Albrier campaigned as the first Black candidate for a seat on the Berkeley, Calif., City Council. Through her work as a key member of the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW) and the Citizenship Education Project, Albrier sought to galvanize coalitions of voting rights activists in California. Height, president of the NCNW from 1957, focused the organization on voter registration in the South. Height, among other civil rights activists, organized the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Black women from across the country activated a movement to ensure Black people and marginalized groups could exercise their legal right to vote.

In 1965, “Bloody Sunday” happened: it was a turning point in the movement. Black and allied activists attempted to march from Selma to Montgomery, Ala., calling for the equal right to vote. But they were stopped by heavily armed state troopers and deputies, who attacked the peaceful protestors on their journey. The event exposed the depth of cruelty and violence in the Jim Crow South to a national television audience and influenced the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 a few months later.

It wasn’t until then — 1965 — that barriers were more significantly removed for Black women to exercise their right to vote. Wright herself was involved with the historic legislation, giving testimony before a congressional subcommittee.

ONWARD

With clarity of vision, and deep gratitude for the sacrifices made by those who came before her, Wright was eager to take on her new role as Election Commissioner in Canton. Wright’s responsibilities included monitoring elections, training poll workers, and supervising registrars. She sued the Elections Board for discriminating against Black candidates and polling staff. She also became involved in education, becoming Vice President of the Institute of Politics at Millsaps College, from 1969 to 1973. Wright then worked for the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission for 15 years and was part of the team that created the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, which opened to the public in 2017.

Wright, and other women of color, in standing up for themselves and those around them, paved the way.

Wright reminds us: “Once you put your mind to something, you can accomplish it.”

The day that I left the courthouse, and I walked down the corridor, I decided that I would run for public office, and I knew that I was going to win it.

FLONZIE BROWN WRIGHT

Article hero image: Flonzie Brown Wright in her home in Jackson, Miss., June 2021. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

Comcast NBCUniversal’s Voices of the Civil Rights Movement platform honors the legacy and impact of America’s civil rights champions. Watch more than 18 hours of firsthand accounts and historical moments online and on Xfinity platforms.

Loading...

Loading...